The beginning of modern Town planning - Sewage

My notes on Germany 1648 to 1806 , Germany 1800 to 1840s , Waikato the golden age 1840s to 1850s , Waikato 1860s , Gentry & Speculators , Water

Starting again with reference to Lewis Mumford’s 1938 book The Culture of Cities (link)

‘There is no proof that visitations of the plague were much worse in the medieval town than in the American or European town of the first half of the nineteenth century’. He states that ‘As early as the sixteenth century provisions were made toward sanitary control and decency in the matter of excrement: thus [John] Stow mentions an ordinance which commands that “no man shall bury any dung or goung within the liberties of the city” (p45). Failure to maintain or enforce hygienic standards had outcomes such as that which occurred when ‘Paderborn was visited by its most serious cholera outbreak in 1851, in which 169 people died. During cholera scares, public health orders demanded the clearing of debris and filth from the city streets. The result was the dumping of large amounts of waste just beyond the gates’ (Germany’s Urban Frontiers by Kristin Poling p95).

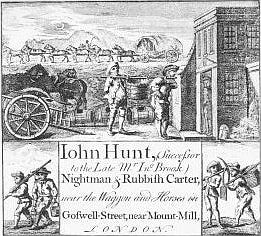

Poling also writes on how Werner Sombart pictured the change up to 1903, ‘He encapsulated this transformation by describing how the borders of city such as Berlin had changed. A century earlier, he wrote, the city was isolated, as if surrounded by a desert. But instead of welcoming the thirsty and dust-blinded traveller, [now] its walls were cloaked in stench of trash, excrement, and the rotting carcasses of domestic animals thrown out of the city’ (Poling, p145). The challenge elected City leaders have is that their supporters like low taxes. ‘In Cologne during the 1850s, awareness of the problem of groundwater contamination led to a new ordinance requiring that sewage be directed into the street gutters instead of being left to seep into the ground; the result was a terrible stench; the better solution, it was soon recognized, was to channel the offending substance out of the city entirely ... with sewer systems, unlike waterworks, there was no hope of profits for the city treasury ... [and] Agricultural interests represented a ... source of opposition to sewer systems, which would deprive them of a traditional source of fertilizer ... petition of a group of vegetable growers seems to have been decisive in a decision by the Dusseldorf city council in 1883 to forbid the dumping of excrement into the sewer ... many cities nevertheless opted until after the turn of the century to exclude human waste from their sewers, requiring instead the regular emptying of latrines and arranging for waste to be hauled away by the city or private contractor.’ (Ladd, p53-56).

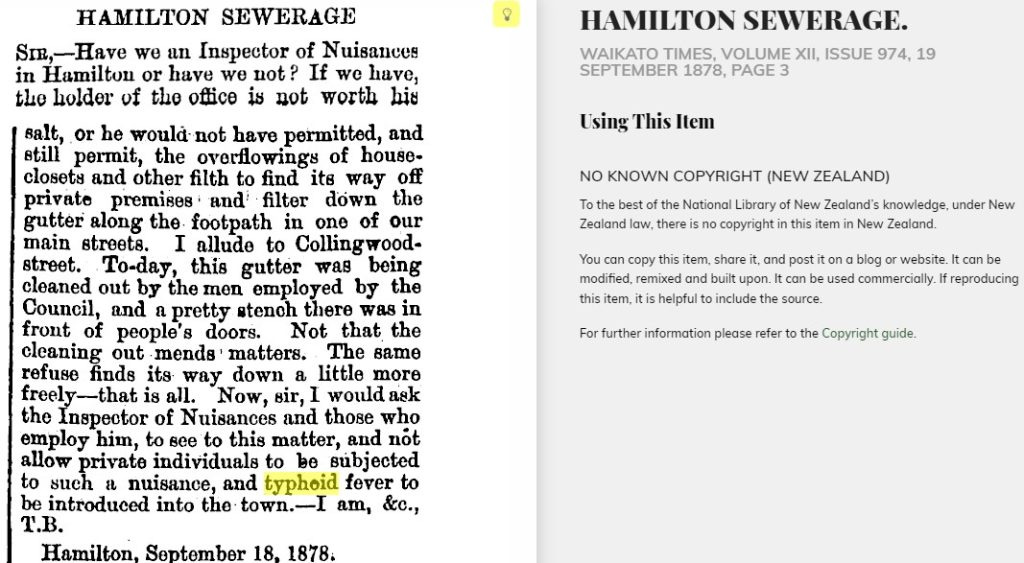

In Hamilton ‘The Collingwood ditch was a great trial. William Davis was charged with using violent Language to one William Woods, threatening to throw him into the ditch, and so on. “Woods, who is a gardener and believes in the value of manure, obtained a permit, and a square shovel, from the Hamilton Borough Council to empty the gutter, from time to time, which runs between the footpath and the roadway, and is known as the Collingwood Street nuisance. When he came near the defendant’s workshop and stirred up the abomination, the aroma was so powerful, that defendant ran out, one hand on his nose, and with the other waving plaintiff away, and sputtering out benedictions, and, withal, threatening to put him in the ditch, if he didn’t clear out there and then.” (Settlers in Depression – H.C.M. Norris, p62)

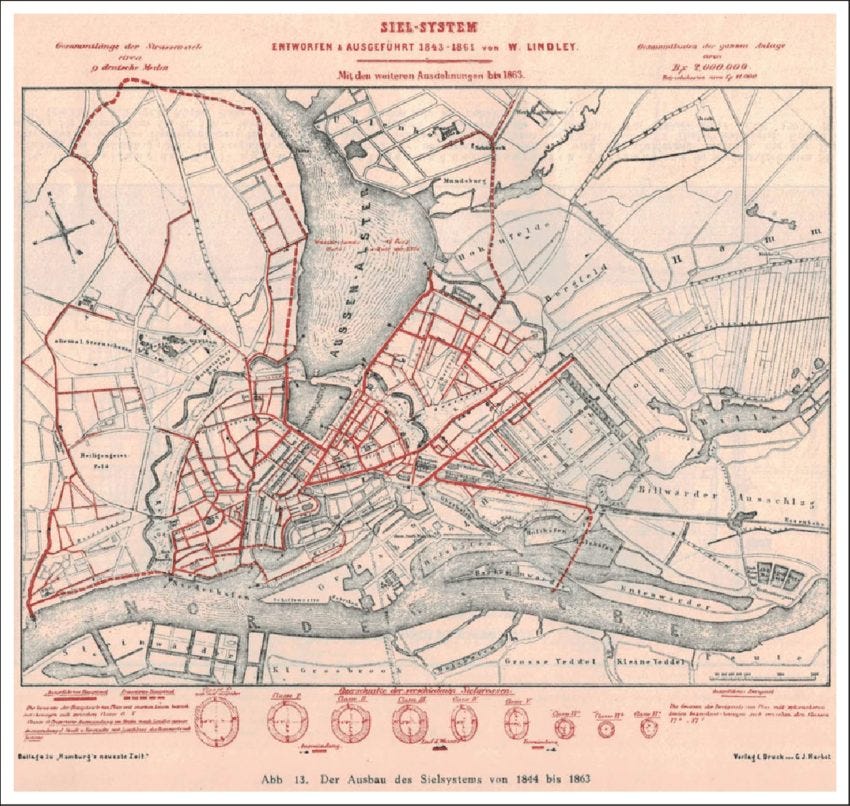

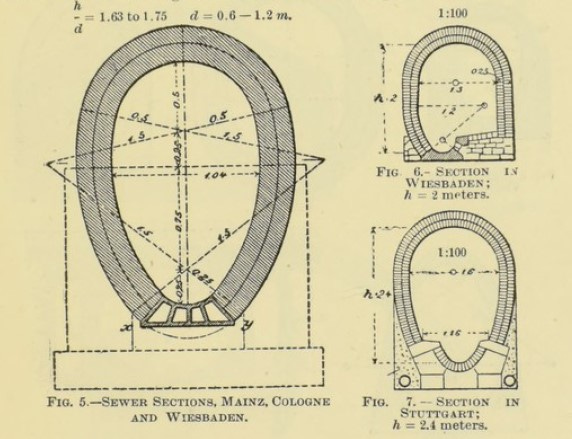

‘The pioneer in sewer construction was ... Hamburg, spurred to swift action by the fire of 1842 and by the leadership of [William] Lindley ... In consultation with [Edwin] Chadwick as well as his fellow English engineers’ (Ladd p54). From projects led by the above named, cities began to build sewerage systems for themselves. An example of the approach can be seen in the 1890s design manual, The Cleaning and Sewerage of Cities by Reinhard Baumeister.

But of course the dung-framer has not gone away - "We humans have a complete misunderstanding of human waste," he says. It's a great fertiliser, full of nutrients. "So why waste it, when I can use it to grow my fruit trees?" from BBC - Why it's time to talk about poo