The beginning of modern planning - Transport

My notes on Germany 1648 to 1806 , Germany 1800 to 1840s , Waikato the golden age 1840s to 1850s , Waikato 1860s , Gentry & Speculators , The beginning of modern planning: Water, Sewage, Housing,

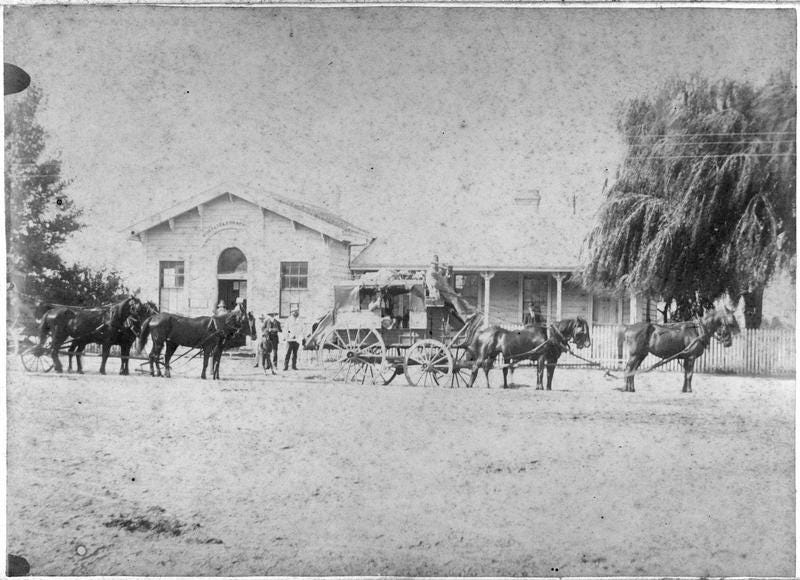

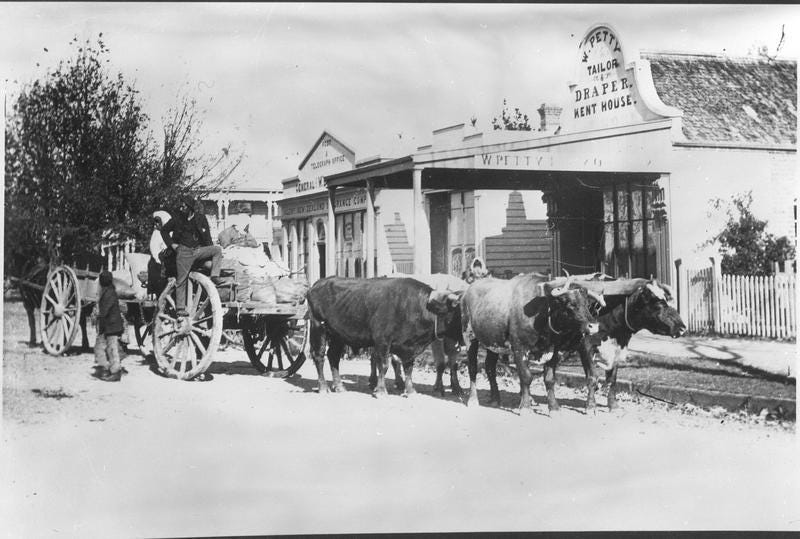

From the 1810s onwards, the safety, reliability and predictability of transport improved, when the Rhine river toll and state of the towpaths was centralised (link 1800 to 1840s), This was followed by the growth of railway companies, with their absolute rights of way and lack of interruption by toll barriers allowing them to operate a system almost literally like clock-work (p125-126 Wagenaar). However, this undermined small-town toll roads, city gate taxes and towns that were not on a planned rail route.

Town Planning in the Netherlands since 1800 by Cor Wagenaar

In the 1840s Engels wrote that Manchester’s upper bourgeoisie in remote villas with gardens, in free, wholesome country air, in fine, comfortable homes, could travel ‘once every half or quarter hour by omnibuses going into the city’ (P58 Engel). A decade later in Germany, ‘Horse-drawn cars pulled over rails laid in city streets first came into widespread [use]... Horse-drawn trams quickly became a part of life in every sizable city’ (p202 Ladd). Cor Wagenaar, in the Netherlands, adds to the tram conversation - ‘the horse-powered Berlin tram was a welcome innovation. It had fixed stops where passengers could get on and off’ (p147 Wagenaar)

The Condition of the Working Class in England by Friedrich Engels - 1840s

Urban Planning and Civic Order in Germany, 1860-1914: Brian Ladd

‘As traffic increased, the city entrances became clogged with huge traffic jams’ (p169 Poling). The boulevards of Paris and the ring road of Vienna had most city leaders looking at repurposing their city wall land to build ring roads. In an 1854 growth plan for Cologne ‘traffic problems assumed the top priority ... [it] incorporated three concentric ring boulevards as well as new radial and diagonal streets’ (p99 Ladd) and widening of streets. In the Netherlands ‘500 kilometres of more or less weather-proof infrastructure for wheeled vehicles, horses, and pedestrians ... the new road system was organized according to a strict hierarchy of state, provincial, and other, minor roads’ (p99 Wagenaar). In the 1850s Rotterdam had planned that ‘streets have a minimum width of 25 meters, and canals no less than 75 meters’ (p115 Wagenaar). Meanwhile, in Amsterdam in the 1860s ‘traffic increased constantly ... an ever-growing number of horses used the streets. The heavier the traffic, the sooner the pavement wore down ... A variety of stones were tested before it was decided that asphalt was likely to provide the best solution ... most traffic, of cause, consisted of pedestrians, and one of the first measures was construction of sidewalks to keep them from being run over by wheeled vehicles’ (p147 Wagenaar). Brian Ladd also references the 1875 fluchtliniengesetz [alignment line law], which ‘permitted municipalities to lay out streets up to twenty-six meters wide without having to compensate property owners for the land taken’ (p104-105 Ladd)

German’s Urban Frontiers; by Kristin Poling

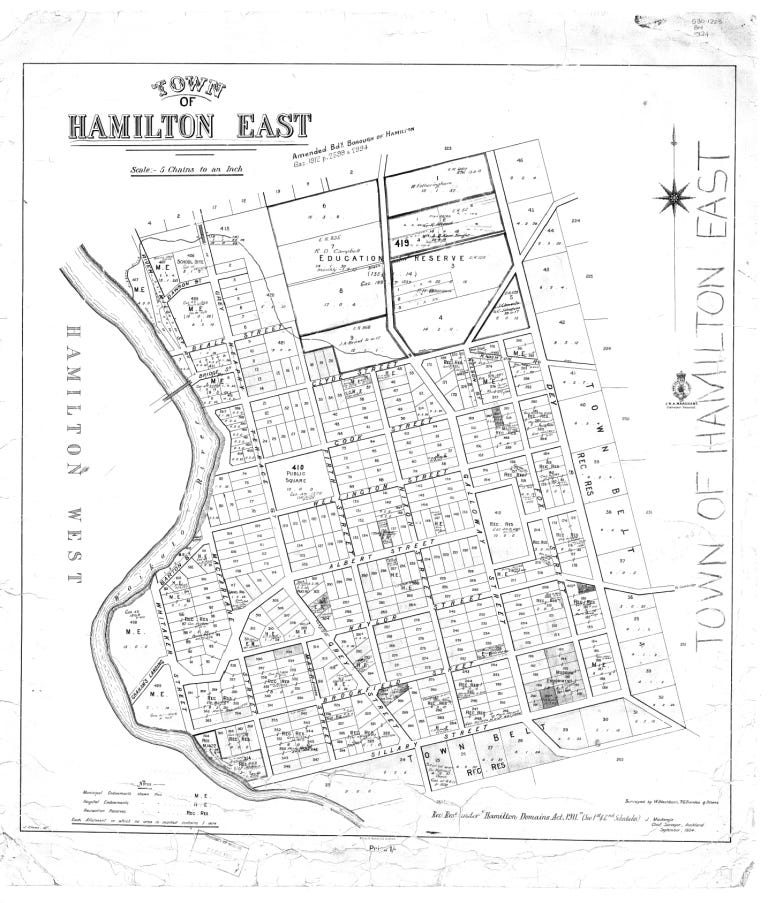

To end, Isaac Coates, mayor of Hamilton from 1888 to 1892, talked of a childhood trip: ‘I remember when going to the Durham County coal mines we had to go through two or three toll bars’ (p22). As a boy Isaac was living in Gayles, Richmond, UK and the nearest coal field I can find was at Ingleton, Darlington, a distance of 20 km (4 hours at walking speed), now days a half hour drive now, with no tolls to pay.

‘On the Record’ - Isaac Coates 1840-1932