The beginning of modern planning - Housing

My notes on Germany 1648 to 1806 , Germany 1800 to 1840s , Waikato the golden age 1840s to 1850s , Waikato 1860s , Gentry & Speculators , The beginning of modern planning: Water, Sewage,

This post covers housing from the 1840s to the 1870s. To summarise: Germany built many large tenements, which became overcrowded. The English build a lot of row houses under single ownership, which after a few decades deteriorated due to lack of maintenance. Amsterdam spread its low-income housing so as not to have large areas of the same type of housing. In Hamilton a small amount of government-led housing was constructed.

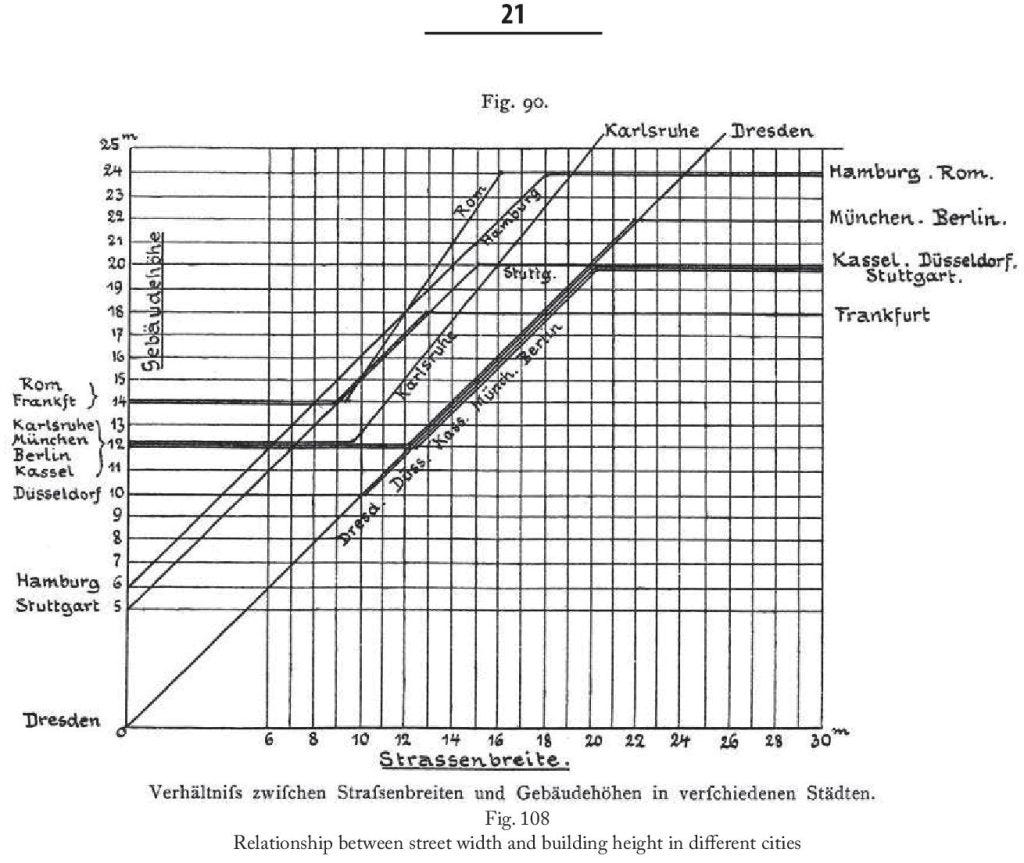

With regard to the quality of housing provided, ‘Quality they understood mainly as a matter of light and air in and around the dwellings’ (Ladd p150). The words “adequate light and air” are repeated throughout Brian Ladd’s book, Urban Planning and Civic Order in Germany 1860-1914. From the 1850s, cities like Berlin, Dussldorf, Hamburg and Cologne adopted ordinances such as ‘the height of building was limited in proportion to the width of the streets they faced; and ... at least one-quarter of the building plot could not be built on’ (p94) ... ‘the pressures of the market led private developers to build as high (typically five stories) and as extensively (three-quarters of the building plot) as the building code permitted’ and many of these buildings became known as Mietskasernen [a description of a tenement which ‘was neither dispensable nor inherently bad’ (p179)] where the number of people sharing a room and using shared toilets was unhealthy. This lead to ‘numerous housing ordinances of the late 1880s and after usually containing provisions requiring a minimum volume of air space per occupant (typically ten cubic metres per adult and five cubic metres per child) and windows offering ventilation and sunlight as well as prohibition against persons of both sexes above the age of fourteen sleeping in same room’ ... [City leaders / reformers] ‘had to face the fact that they were calling into question the ability of the free and private market to house the poor decently (p145) ... The most popular solution of the day was non-profit building societies. These were private companies, but they usually had some kind of municipal support (p147).

Notes from The Condition of the Working Class in England by Friedrich Engels - 1840s

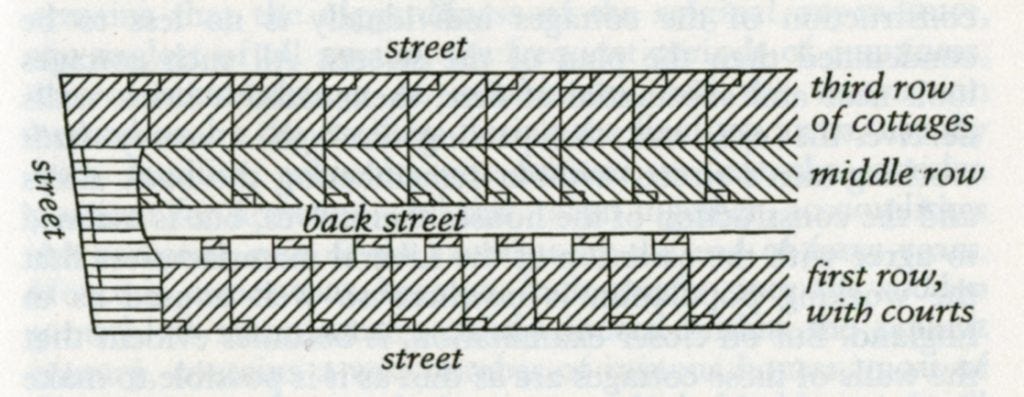

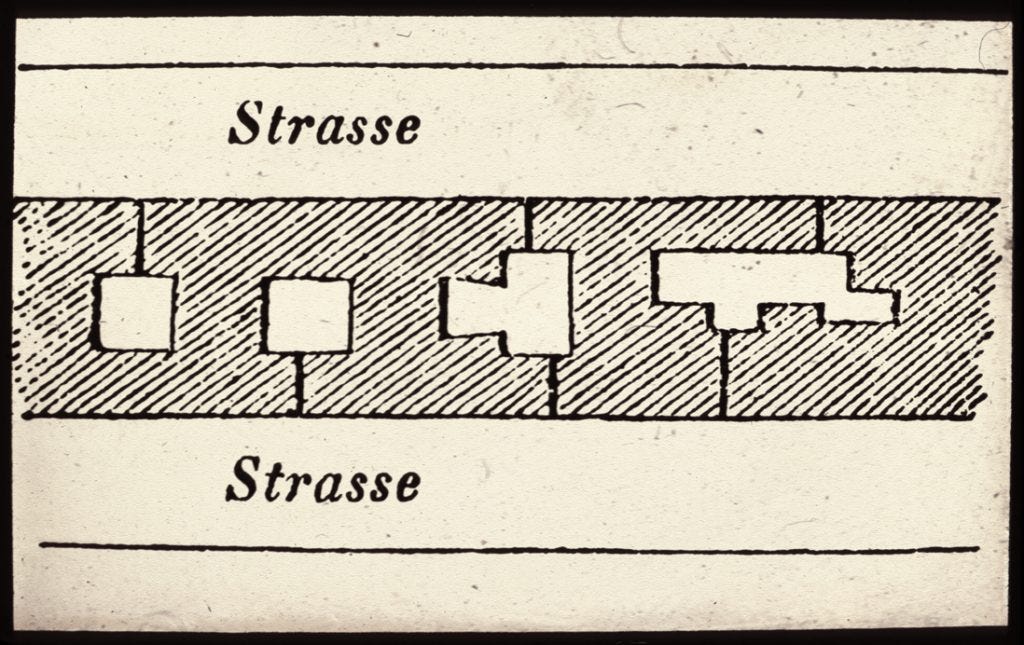

‘In Nottingham there are in all 11,000 houses, of which between 7,000 and 8,000 are built back to back with a rear party-wall so that no through ventilation is possible, while a single privy usually serves for several houses (p49) ... Working-men’s cottages are almost never built singly, but always by the dozen or score; a single contractor building up one or two streets at a time. These are then arranged as follows: One front is formed of cottages of the best class, so fortunate as to possess a [front door and] back door and small court, and these command the highest rent. In the rear of these cottages runs a narrow alley, the back street, built up at both ends, into which either a narrow roadway or a covered passage leads from one side. The cottages which face this back street command least rent, and are most neglected. These have their rear walls in common with the third row of cottages which face a second street, and command less rent than the first row and more than the second ... By this method of construction, comparatively good ventilation can be obtained for the first row of cottages ... The middle row, on the other hand, is at least as badly ventilated as the houses in the courts, and the back street is always in the same filthy, disgusting condition as they. The contractors [owner of the dwelling] prefer this method because it saves them space, and furnishes the means of fleecing better-paid workers through the higher rents of the cottages in the first and third rows (p68) ... The contractors [owners of the dwellings] never own the land but lease it ... [at the end of the lease] everything upon it [the land, goes] back into the possession of the original [land-owner], who pays nothing in return for improvements upon it ... It is calculated in general that working-men’s cottages last only forty years on average’ (p70) ... So land was leased for 40 years, the newly built ones with their massive walls looked beautiful, during the final ten years what remain was neglected of all repairs, the frequent periods of emptiness, the constant change of inhabitants to the point residents do not hesitate to use the wooden portions for firewood – all this, taken together, accomplishes the complete ruin of the cottages by the end of forty years’ (p71).

In Amsterdam, 1866 - 'public housing was distributed over all five parts, thus preventing the emergence of a large area with only low-cost housing. The project was driven by technological solutions for what were mainly hygienic problems’ (p148). From Town Planning in the Netherlands since 1800, by Cor Wagenaar

The following notes are from Armed settlers: The story of the founding of Hamilton, New Zealand, 1864-1874

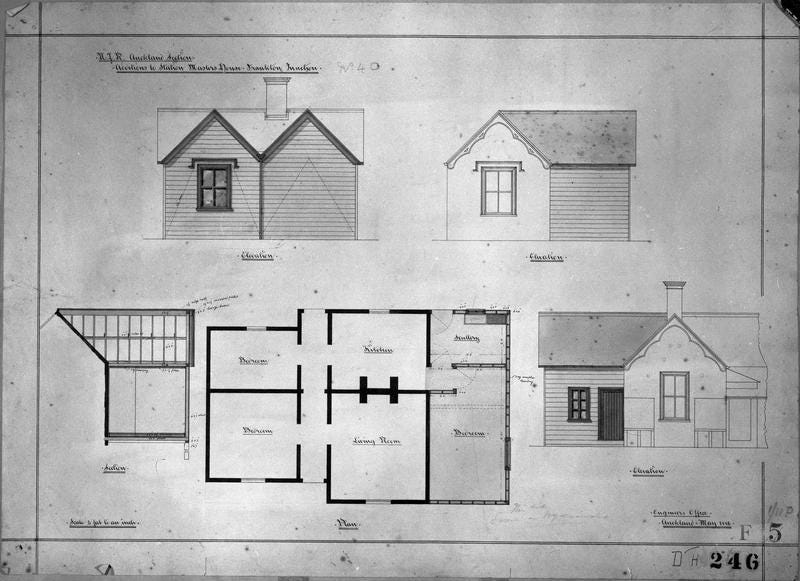

In the 1870s the Provincial Superintendent had ‘prefabricated’ cottages manufactured ... Built of heart of kauri with a corrugated iron roof, iron fireplace and iron chimney, these four-room cottages were twenty-three feet by twenty feet in size. There was no bath, tank, or water closet ... eight of these were erected at Hamilton, four on each side of the river (p22) ... Hamilton East had a population of 169 males and 131 females. The figures for Hamilton West were 200 and 166 ... in Hamilton East there were fifty-three wood and iron dwellings and two sod huts. Eleven houses had less than three rooms, The number of houses in Hamilton West was seventy-one. (p226)