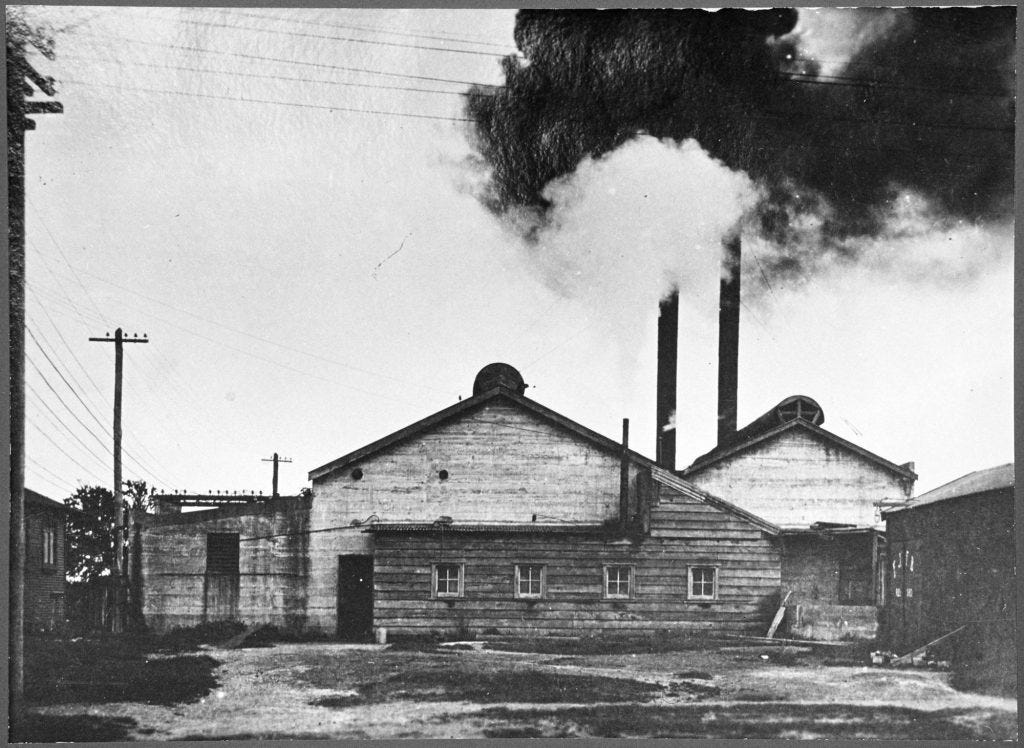

Hamilton by the early 1910s

My notes on Germany 1648 to 1806 , Germany 1800 to 1840s , Waikato the golden age 1840s to 1850s , Waikato 1860s , Gentry & Speculators , The beginning of modern planning: Water, Sewage, Housing, Transport, City Centre, Markets and Zoning, 1890s: Introduction, Dwellings & Lots, Reason for Zoning, Horses, Cyclists & road deaths, York, City beautiful & genesis of motorways, Garden City, Dresden 1903, Chicago 1909

Hamilton NZ, as a town, was drawn up for the benefit of property speculators. Kirikiriroa and its surrounding villages exist because the ‘Waikato lands were of unrivalled fertility’ (Gibbons p.29) and the owners knew they were making good money from working it. This was something the British had frequently done before. English and European history lists many ‘profit-driven ‘bad buggers’ like Sir Frederick Whitaker, Thomas Russell, & Co (Link – toti) who just took land.

Astride the River by P.J.Gibbons

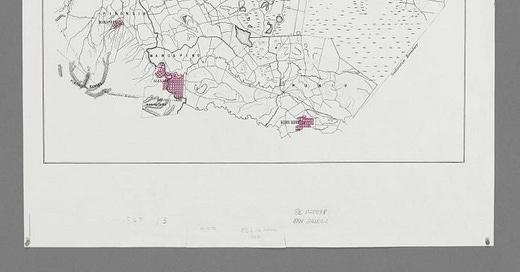

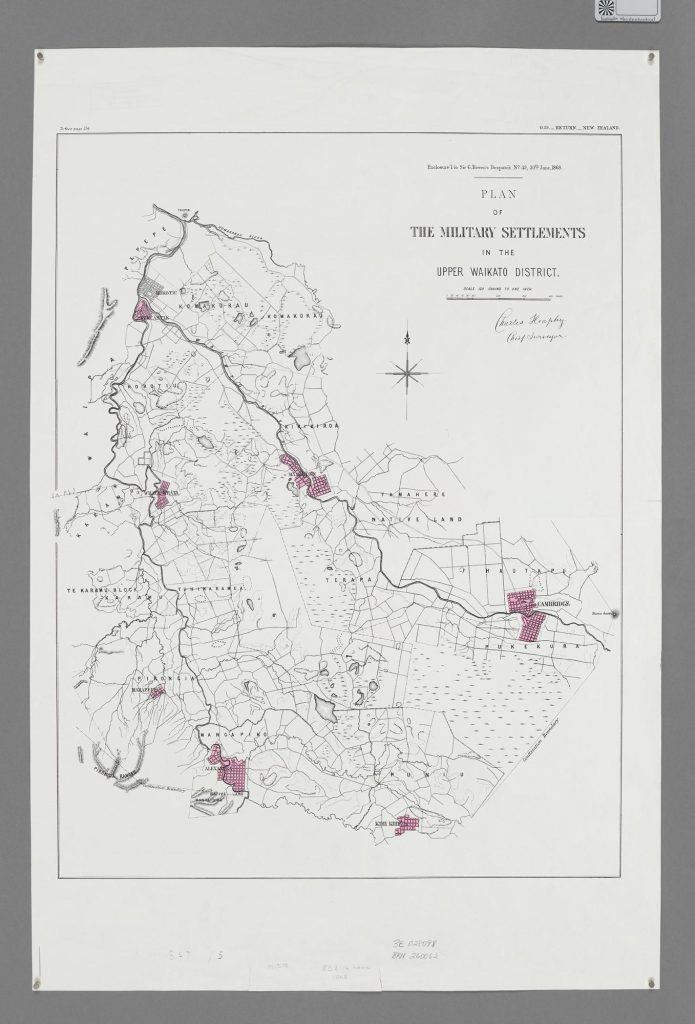

The 1860s plan for Hamilton was based on a predictable grid pattern, with a town belt. In the East we have Galloway Park, Education Reserves, and a Town Square, which attracted the Methodists to build a church facing it. The Freemasons did the same, and on the northern side there is/was a mix of business, housing and education. Hamilton East businesses expanded from the intersection of Clyde St and Grey St. In the West businesses grew up from Grantham Street, then north along Victoria and west up Knox St, Hood St, and Collingwood St: residential areas changed to retail and business as land values increased. The Government built its buildings on the south side of Knox Street. The Anglican St Peter’s church (later cathedral) was built on high ground, as was the Catholic Cathedral facing Bridge St - both choice locations that gave them good vistas, without the Public Square as in European cities. The Hospital, on a hill away from the city centre, had unrestricted access to air and light.

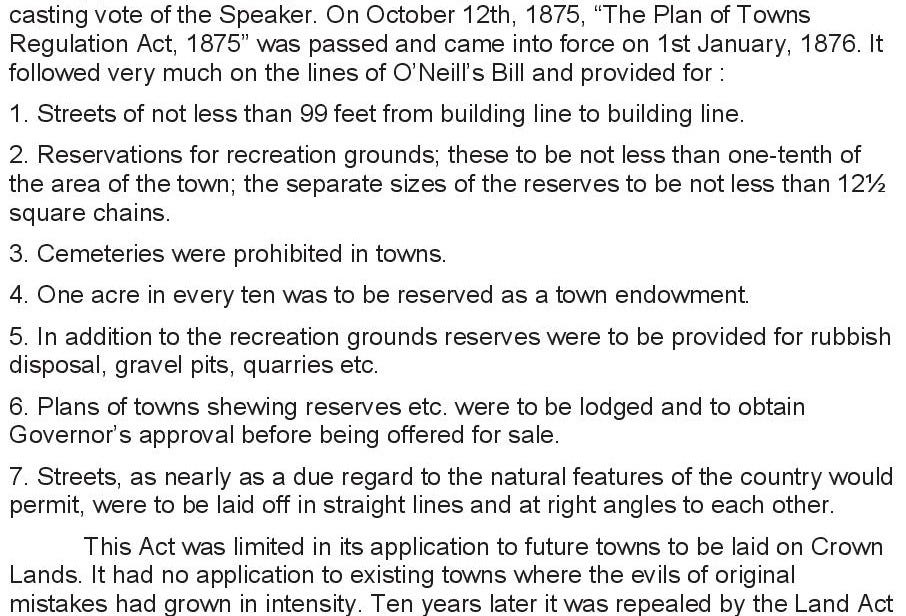

Laws – The year 1866 ... Cattle wandering in search of feed destroyed the crops of neighbours, and a public pound was opened (Armed Settlers p.160). In the 1870s board began ‘enforcing the Weeds and Watercourses Act of 1866 (which meant cutting out the flourishing gorse and keeping drains clear)’ (Gibbons p.63, 66, 69). In 1871, to make the town look less rural, ‘Stock were to be permitted in the township by permission of the board after various fees had been paid’ There was also a resolution permitting the pound-keeper to carry off to his pound any sheep, pigs and goats found straying ... Ultimately all livestock, horses and cows, as well as pigs, sheep and goats, would disappear’ (Gibbons p.66, 68). By the turn of the century, ‘The bylaws hedged animals somewhat but failed to control them adequately ... Cattle and pigs frequently wandered, through residential and business areas ... Dogs, supposed to be registered, were always a problem. Horses, properly attended or hitched when left, were of course not prohibited (Gibbons p.106 also see ‘Settlers in Depression’ p.93). As all new towns do after a fire wipes out a large part of a town, an 1899 Fire bylaw was passed – ‘requiring new buildings in the central business area to be of permanent materials’ (Gibbons p.109). The ‘Public Health Act of 1900’ provided for a local health officer and the enforcement of health laws. Several houses in Hamilton were condemned as unfit for habitation. In most cases these places were not owner-occupied. ‘They belonged to citizens who lived in reasonable circumstances’ (Gibbons p.107) as was the case in most cities. Rates – ‘In 1901 the system of rating was changed from an appropriation on capital value to one on unimproved value’ (Gibbons p.110) (for more on land tax read ‘Progress and Poverty’ by Henry George from 1879 – ‘tax upon the value of land is the best tax that can be imposed’ p.414). ‘In 1906 the borough council introduced a building permit system, which was used to enforce certain standards of design and construction’ (Gibbons p.125).

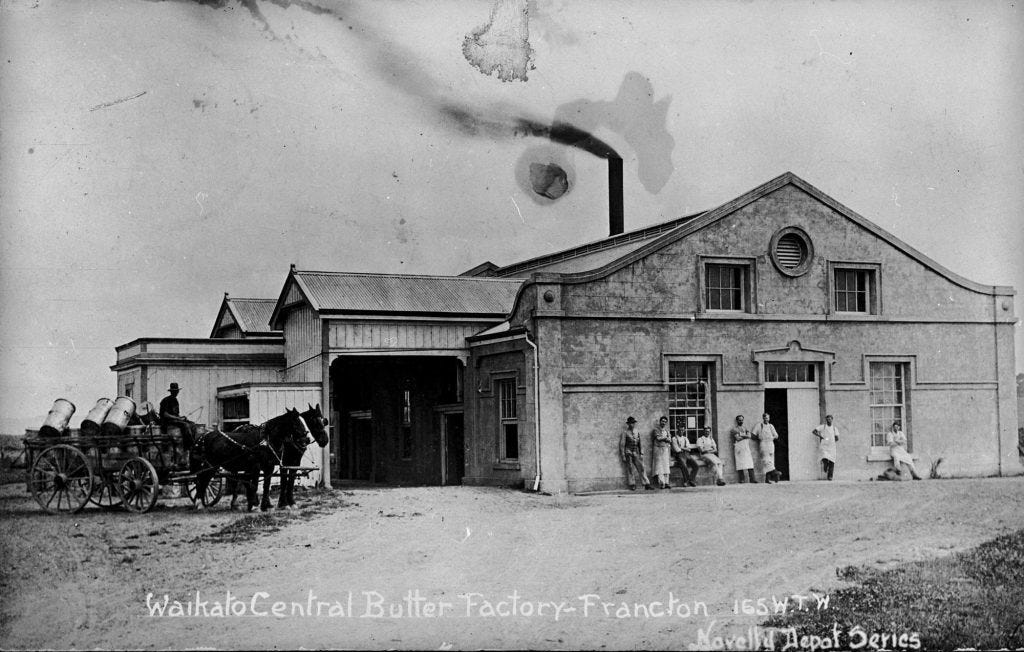

Infrastructure – From the start, road / highway boards were established to prioritize road building, but the success of Hamilton came from the Frankton Junction, a railway complex that meant ‘by 1910, over eighty trains passed through Frankton Station daily’ (Gibbons p.153). Other infrastructure such as a municipal water supply (and mains pressure thanks to Frankton), sewers and electricity (again thanks to Frankton), basically meant that Hamilton, with a population of about 6,000 people in the mid-1910s, had access to the same information and infrastructure that English and central European cities had.

Drivers and Cars – In the 1870s a man was imprisoned for being ‘drunk in charge of a horse and cart’ and in 1878 the council thought it ‘desirable to have by-law to compel vehicles passing through the borough at night, to carry lighted lamps’ (Settlers in Depression p.63). The Waikato Times reported, early in 1904, that ‘a greater number of motorcars has been seen in Hamilton than at any other time before, and consequently the dwellers even in such an equestrian part of the world as this are forced to ask themselves: Is the horse doomed to extinction? (Gibbons p.147). There was also a speed limit of 9.3 kilometres an hour for motor vehicles (Gibbons p.132).