Ground floor - Mixing Retail and residential - History

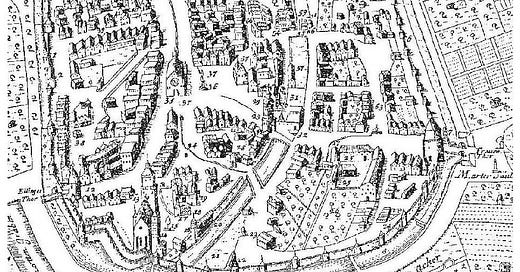

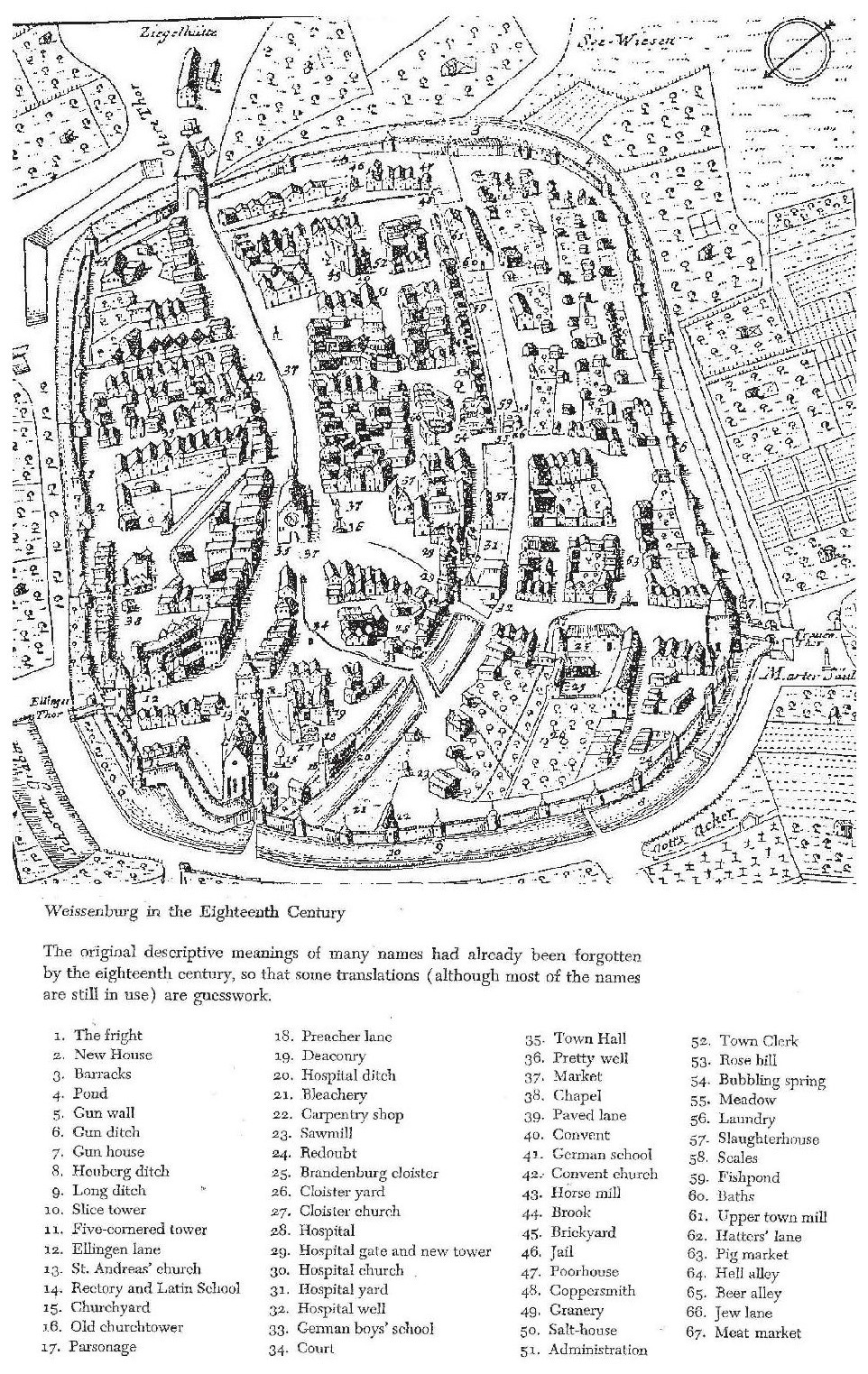

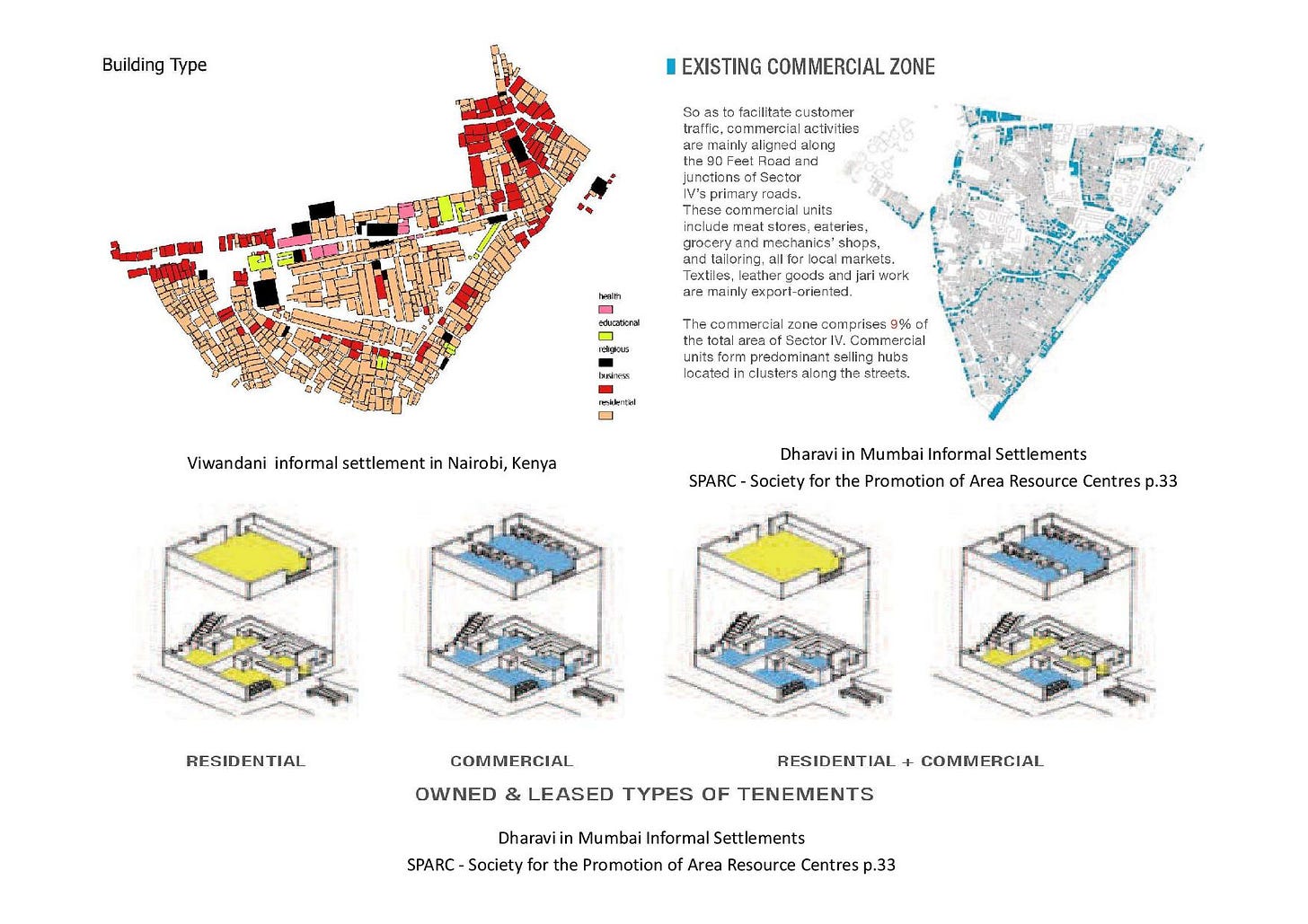

The mixing of retail and residential use of buildings at ground floor level is normal in many cities around the world. In Hamilton this is not permitted because it is seen as ‘unattractive’. This post provides the origin of this thinking, starting and ending by quoting Friedrich Engels: ‘For the thoroughfares leading from the Exchange in all directions out of the city are lined, on both sides, with an almost unbroken series of shops ... this hypocritical plan is more or less common to all great cities ... thoroughfares, so tender a concealment of everything which might affront the eye and the nerves of the bourgeoisie ... [by not mixing residential, provides] the eager assurances of the middle-class, that the working-class is doing famously ... the “Big Wigs” of Manchester, are not so innocent after all, in the matter of this shameful method of construction’ (p.58, The Condition of the Working Class in England by Friedrich Engels. 1845). The next reference, from the 1890s, provides a context for what contributed to future planners’ thinking: ‘In the Middle Ages whole streets or quarters of the city were frequently devoted to the trades and it was customary for men working at a certain trade to group themselves together. Old street names like “Löhergraben” [Tanner], “Kupfergasse”[Copper Alley], “Hutmacher” [Hats] etc. remind us of this segregation of the trades and classes that is no longer customary today. In modern places tradesmen are scattered all over the city among the other inhabitants... Although promenade and “luxury” streets are too expensive to afford suitable dwellings for tradesmen it is not uncommon to find craftsmen living on the ground floor’ (p.333 City Building by Joseph Stubben. 1890). From the 1910s the stories American planners told of main streets were of mixed and changing places: ‘The lots along the main streets are being used for store and tenement purposes’ (p.43/78pdf Bridgeport J. Nolen ), In early approaches to zoning, a lot of the story related to residential ‘districts [zones] in which business is forbidden’ (p.143/180pdf, Better City Planning for Bridgeport by John Nolen, Consultant on City Planning, 1916), and in other cities it was Industry not residential that was of concern - ‘North Main Street likewise is in a transitional stage from residences to stores, especially north of Central Street. Industries occupy part of the frontage on this street, producing breaks in the development to the disadvantage of retail store expansion’ (p.10 Survey & City Planning Proposals Bristol CON by J Nolen, 1920).

Early modern planners expected residential living in commercial zones and had little or no comment on which floor they would live on – ‘Light industrial and commercial – This district [zone] would permit all business, houses, stores both retail and wholesale, office buildings and certain types of light and unobjectionable manufacturing’ (p.110, Decatur Plan by Edward Bassett, 1920). But they imagined a past in which ‘The oldest towns had their different quarters or bazaars: the butchers tended to congregate in one section, the jewellers in another, the cloth merchants in another, because experience showed this was best for business. Zoning simply utilizes this age old experience and applies it logically and in orderly fashion’ (p.21, Quoting John Ihlder, in the Elkhart Plan by John Nolen, 1923). This is a fictional utopia: ‘oldest towns’ that do not exist. Visit any century’s old town or informal settlement, and you will find a mix of congregated and scatted commercial activity. The street and neighbourhood names came from different eras, and sometimes the street name came from a single merchant . Zoning as proposed in the 1920s was based on the blending of generalised facts and opinion, the sort you might find in a dramatised documentary. Planners unashamedly accuse others of using ‘propaganda’ and using it themselves (references below).

p.28 - Decatur 1920 by Myron Howard West

p.105, 153, 241, 303 - Walpole 1919 by Charles s. Bird

p.115, 250, 251, 270 - NZ Planning Conference 1919

By the late 1920s the idea behind the proposed Melbourne ‘Plan of General Development (1929)’ was to regulate development on modern scientific lines’ (p.4) and to ‘prevent the indiscriminate mixing of residences, factories, and shops ... Stabilizing the value of property’ (p.155). An earlier ‘local Government Amending Act 1921 empowers municipalities to declare residential areas within their boundaries ... these areas prohibit the use of land for other than residential development’ (p.155). The 1929 plan explains the reasoning for restricting mixed use, with my emphasis - ‘the sandwiching of shops and residences, and the resultant mixed development, has a depreciating effect on both forms of use and renders unattractive many of the main roads ... It frequently happens that where shops have been erected in excess of local demands, the shop is a consideration secondary to the dwelling attached. On account of off-setting the rent by the shop returns, people are induced to live under conditions which would not be tolerated in other portions of the municipality ... This wasteful development will be prevented by the operation of a zoning scheme, which aims at defining business areas in accordance with the probable future demand for shops’ (p.160).

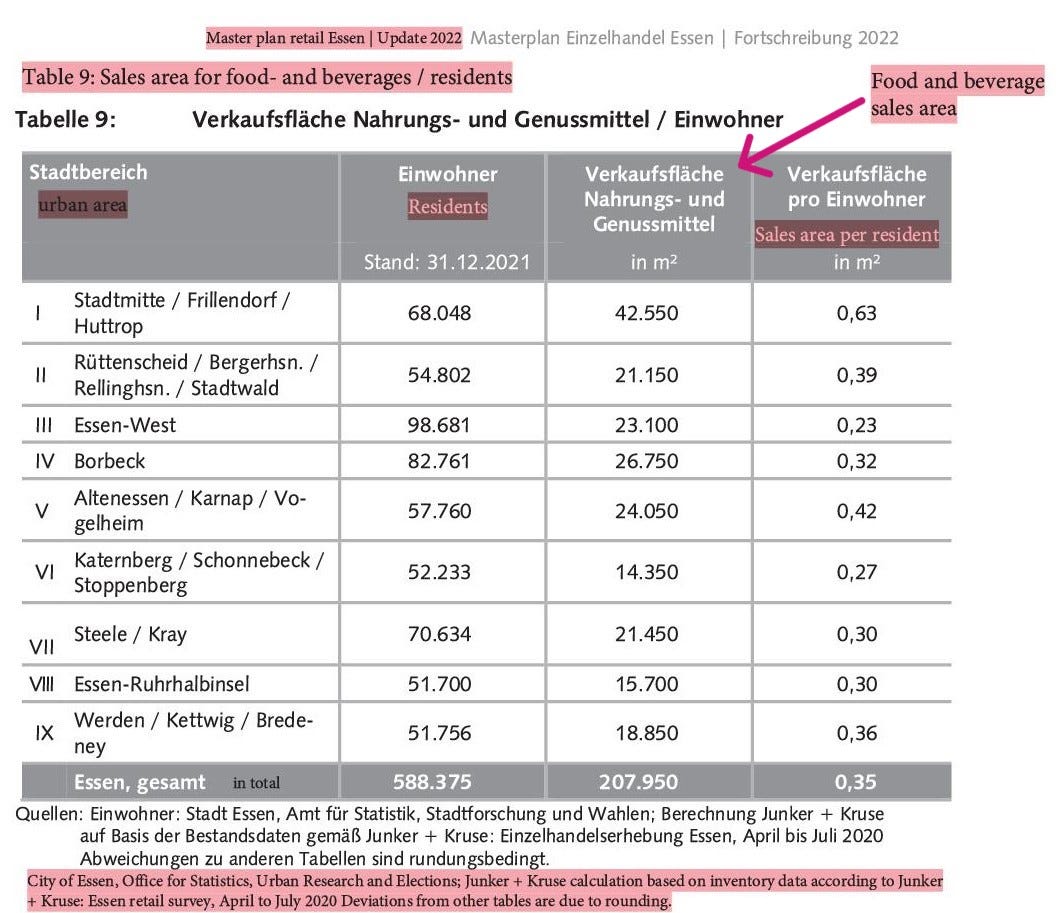

The planned ‘scientific’ measure used for ‘the probable future demand for shops’ (p.160) was to plan for ‘one shop for every 50 of the estimated total population’ (p.252). This number comes from ‘data supplied by the Department of Labour ... giving the ratio of shops to population in the various municipalities in the metropolitan area’ (p.158). The data are from 28 neighbourhoods, with the ratio being one shop per 25 persons to one shop per 82 persons, the average being one shop per 44 persons, and the proposal use the median, this being ‘one shop per 50’ persons. So here is the BS: the problem was ‘Speculative Land Subdivision – The subdivision of too much land into business sites in the suburban areas has been one of the chief causes of the somewhat unsatisfactory development of business streets’ (p.159 Melbourne 1929). It still possible to build one shop per 50 persons and have demand for only one shop per 82 persons; i.e., ‘too much land into business’. Ebenezer Howard, in his book ‘Garden Cities of Tomorrow’ explains the problem of allowing too many shops: ‘In many cases the effect of competition is to make a rise in price absolutely necessary ... Thus the competition of shopkeepers, absolutely tends not only to ruin the competitors, but to maintain and even to raise prices, and so to lower real wages’ (Howard p.80-81).

The latest reasoning for not permitting mixed use ground floors in Plan Change 12 is that ‘Streets that do have an active street frontage are key transport corridors for the city, with high levels of existing retail and commercial activity. Residential activity on the ground floor in these areas would be inappropriate ... It would be highly likely that residents on the ground floor along these key corridors and intersections would create privacy measures by reducing visual permeability into potential apartment spaces when compared to retail and commercial activities on the ground floor, thus reducing the active street frontage desired ... outcomes that support a well-functioning urban environment’ (p.34*). Meaning the desired outcome is that ‘the thoroughfares … of the city are lined, on both sides, with an almost unbroken series of shops’ (p.58, Friedrich Engels, 1845).

*HCC Plan change 12. Denzil Govender 26 June 2024 Structure plans Central City and Rototuna Town Centre.