1910s City planning: Columbus, Rochester, and Seattle

My notes on Germany 1648 to 1806 , Germany 1800 to 1840s , Waikato the golden age 1840s to 1850s , Waikato 1860s , Gentry & Speculators , The beginning of modern planning: Water, Sewage, Housing, Transport, City Centre, Markets and Zoning, 1890s: Introduction, Dwellings & Lots, Reason for Zoning, Horses, Cyclists & road deaths, York, City beautiful & genesis of motorways, Garden City, Dresden 1903, Chicago 1909, 1910s: Hamilton,

The purpose of this blog post is to identify where early District Plan rules originated from. Like Germany and England, many American cities had doubled in size over a few decades. Unlike German city plans, which were led by local politicians and bureaucracies, in American cities, committees were funding consultants to write reports for their city. This post covers city reports from Columbus, Rochester and Seattle.

Columbus Ohio had a population 88,150 in 1890, which more than doubled to 181,511 in 1910. This Columbus report is a study of ‘civic improvement ideas’ (Columbus p.21). I will highlight four ideas from this report. (1) ‘At the intersection of radial streets, there are to be created oval spaces which shall be developed as neighbourhood centres, that will be used for street-car transfer, for local shopping, and especially for the public and semi-public buildings of the neighbourhood‘ (Columbus p.27). (2) There is a idea for a ‘law [that] prohibits the erection of billboards within a certain distance of any park, parkway or boulevard’ (Columbus p.35), (3) Schools – ‘it is unwise to build large primary schools ... as children attending primary schools should not be compelled to use cars, many small schools are better for them than are a few large ones ... School sites should be developed in connection with open spaces, parks and parkways’. (4) Another law that ‘prohibits the opening of a saloon or a barroom’ within several hundred feet of a public school is an excellent one (Columbus p.37).

The plan of the city of Columbus: report 1908

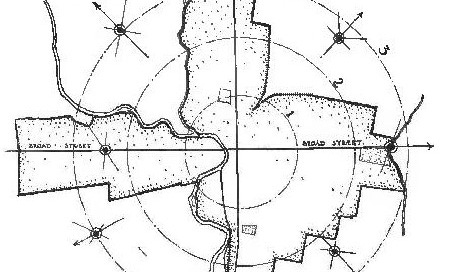

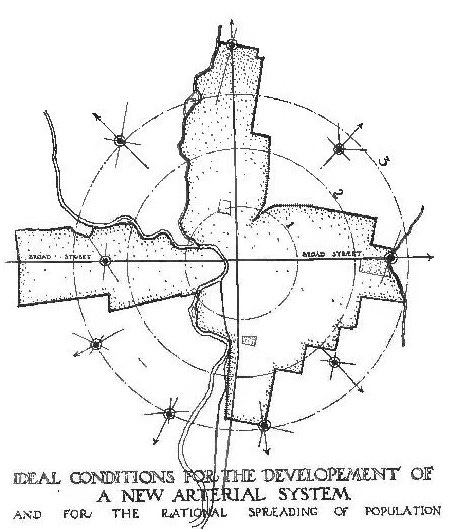

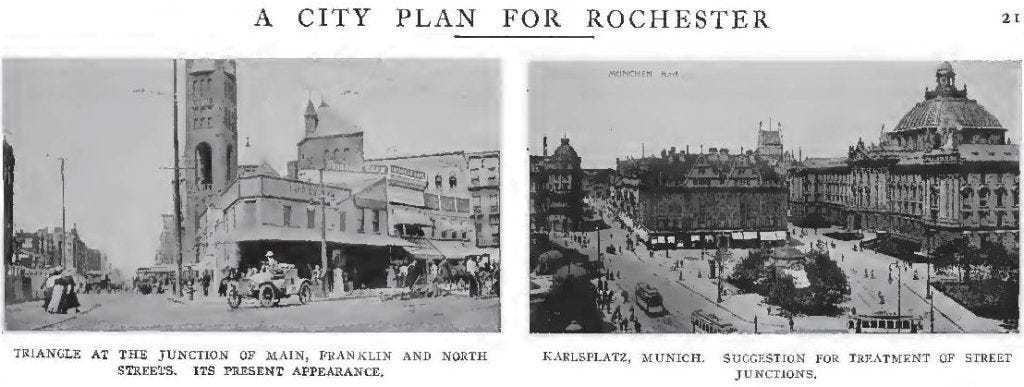

Rochester New York had a population of 89,366 in 1880: by 1910 it had increased to 218,149. Introduction to the report - ‘with the growth of the city the pressure of opportunity for immediate cash savings and immediate cash profits, with the pressure of rising land values, will tend more and more to depress the standards of healthful and comfortable housing and living ... It lies in the City's own hands to fix an arbitrary minimum in regard to many of the conditions controlling the healthfulness and agreeableness of the people's habitations and places of work, and thus to prevent those who cannot, or who foolishly will not, rise to that minimum standard from competing directly with those who do. ... In every city the freedom of the individual must often be sacrificed for the good of the community; that, as a city grows, municipal control or regulation of private activities is more and more needed to safeguard the public welfare ... in this report it has been our aim ... to preserve the one [characteristics of Rochester] and stimulate the other [the natural lines of its growth]; and not to force improvements alien to the city’ (Rochester p.13-14). From this report I find five points to note. The first is similar to what we find in Hamilton with the Waikato river (1) ‘The River in the Heart of the City THOUSANDS of visitors come to Rochester and do business ... on Main Street, and never know that there is a river near them, so completely is it blanketed by the buildings which have been built over it along the Main Street frontage. Aesthetically, this loss of the river is most unfortunate’ (Rochester p.22). The second note helps to understand how the report aims to preserve the characteristics of the city and how growth can be achieved (2) Land supply – ‘The supply of land on the outskirts is unlimited’ (Rochester p.32). (3) ‘Main thoroughfare - even of the most compact type, must provide for car tracks [trams] in the middle. Then, on every busy thoroughfare vehicles must be free to stop for loading and unloading; the space next the curb thus becoming a mere series of stopping places for vehicles doing local business ... essential to provide space for at least one free line of through travel in each direction between the cars and the slow-moving or standing vehicles next the curb ... it must be remembered that a main thoroughfare is apt in time to become a retail trading street, and wide sidewalk space is therefore important ... eighty feet [24m] is about the least width within which the above requirements can be met ... ninety feet or 100 feet [30m] between building lines is decidedly better’ (Rochester p.32). (4) Building set-back – If a single property owner on a residential street ‘wants to put in a store ... before the City is ready to widen the street to increase its traffic capacity ... he must not move forward of the general building line’ (Rochester p.34). (5) Parks – ‘local recreation needs of a city, is that every family to be served must be within easy walking distance of the park which is to supply its needs. And by easy walking distance is meant a distance so insignificant that it will not deter the little child, or the tired mother with a baby, from going to the park for half an hour's recreation when the chance comes. It is doubtful if these people can be expected to walk more than a quarter of a mile [400m] (Rochester p.42).

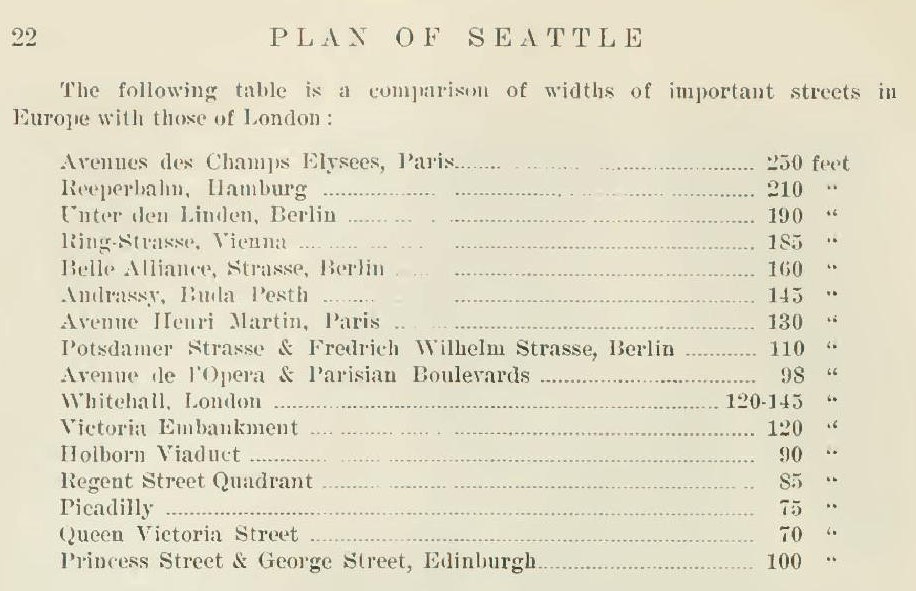

Seattle, Washington’s population was more than doubling each decade; in 1890 it was 42,837 increasing to 80,671 at the turn of the century in 1900, and then 237,194 in 1910. The ‘plan provides for the "future demands" of the city, and for the inevitable large increase of population, it was decided that the plan should embrace an area of about 150 square miles, with 7,000 inhabitants per mile [11 per acre or 27 per hectare or 2,703 per km2] ... Seattle—would provide for a population of slightly over a million inhabitants’ (Seattle p.14). My reading finds the authors of this report are impressed with European cities: ‘Dresden, Berlin, Vienna, Stuttgart and Buda Pesth ... have, within a quarter of a century, become model towns in every respect’ (Seattle p.18). Further reading shows much of the focus is on road widening, especially very wide ones (see image above). ‘The width of this parkway should be from 300 to 500 feet [152m] ... [Boulevards] for this purpose a width of at least 160 feet [48m] should be provided (Seattle p.43). Of course the report mentions – ‘The hazard from fire is so notorious that no comment need be made’ (Settle p.52), because every city will have a great fire before enforcing fire prevention in the town planning rules.