<strong>1890s - City Building - Introduction</strong>

My notes on Germany 1648 to 1806 , Germany 1800 to 1840s , Waikato the golden age 1840s to 1850s , Waikato 1860s , Gentry & Speculators , The beginning of modern planning: Water, Sewage, Housing, Transport, City Centre, Markets and Zoning

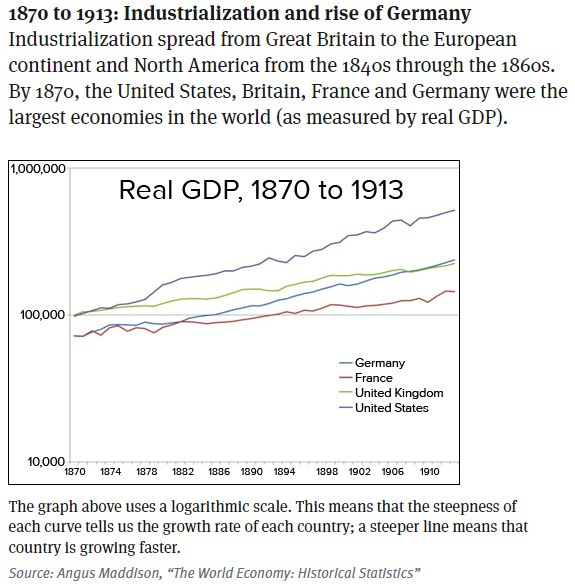

According to Brian Ladd in his book Urban Planning and Civic Order in Germany, 1860-1914, ‘by the 1890s, nearly all the elements that ultimately composed modern city planning, from sewers and water supplies to ambitious attempts to coordinate the layout of streets and construction of housing in a healthful and orderly manner’ (Ladd p. 43) were present. However, city planning ‘was not planned for the urban poor but rather for the city’s wealthy ... [that] envisioned a return to lower-density settlement’ (Poling, p. 137).

Germany’s Urban Frontiers by Kristin Poling

In German cities ‘a three-class voting system was devised that made sure the Committee represented all the citizenry evenly, as follows: one third of each Committee was to be chosen from among the highest-taxed third of the citizenry, one third from among the next highest-taxed-third, and the last third from among the lowest-taxed citizens’ (Walker, p. 275 & p. 343). However, the vast majority of taxpayers fell into the last group, where a minimum tax payment was usually required of voters (Ladd, pp. 21-22). The view was that ‘the rootless poor were a political threat; that the right to vote was not a right to vote for one’s own interest but for the common interest, and the poor would be more tempted to vote for their own interests than would the securely established’ (Walker, p. 342). However the upper third comprised a mere handful of voters. The ‘Hessen-Darmstadt area made a rule that the highest-taxed person in any community automatically became a full member of the town council’ (Walker, p. 407) and in Essen ‘the head of the Krupp family alone elected a third of the city council’ (Ladd, p. 22).

German Home Town, 1648-1871, by Mack Walker

In the Netherlands in the 1840s there was a ‘shift from France as the most important source of inspiration for architecture and urban planning to Germany’ (Wagenaar, p. 153). Although Dutch architects and urban planners did not ignore developments in other countries, notably England and the United states, they focused almost entirely on Germany’ (Wagenaar, p. 158). ‘By the end of the nineteenth century, Germany cities enjoyed a global reputation for excellence’ (Ladd, p. 112). Internationally there was also acknowledgement of ‘the spectacular growth of English cities’ (Ladd, p. 36), which was also happening in cities around the world. Scientific surveys on cities by the English social reformer Edwin Cadwick from the 1830s (Ladd, p. 54 and Wikipedia), the ongoing poverty surveys being undertaken by Charles Booth in London, and reporting on the horrors of tenements in New York by Jacob A. Riss in his 1890s book ‘How the other half lives’ could not go unnoticed.

Town Planning in the Netherlands since 1800 by Cor Wagenaar

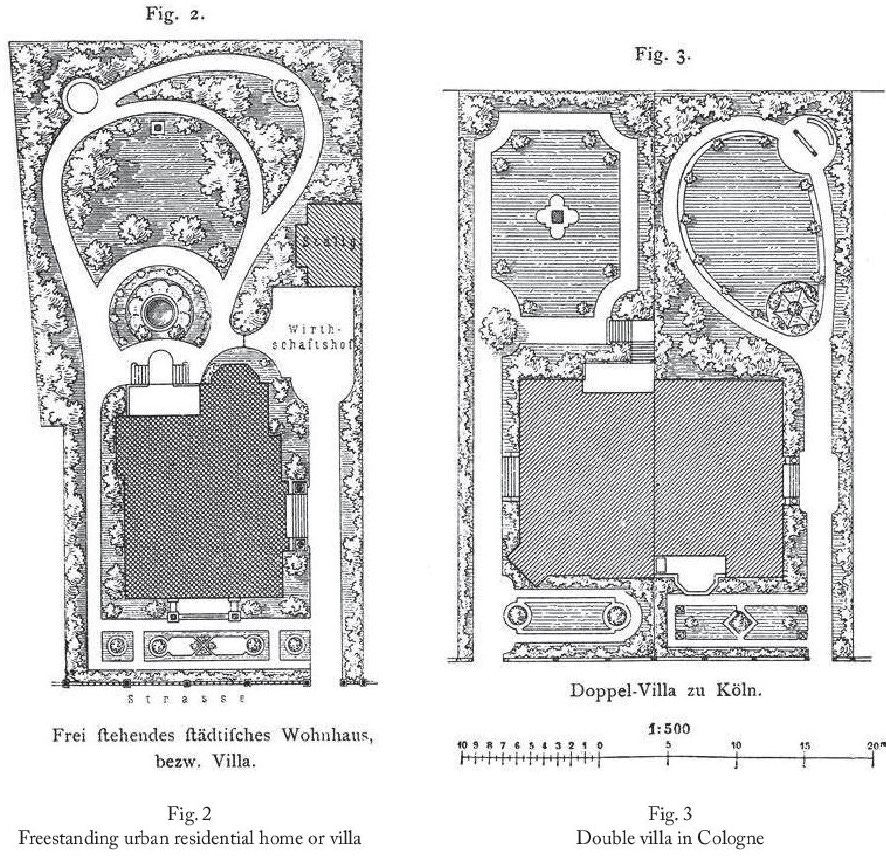

Reinhard Baumeister’s influential book Stadterweiterungen in technischer, baupolizeilicher und Wirtschaftlicher Beziehung (Town extensions: their links with technical and economic concerns and with building regulations) published in 1876 ‘is often considered the first textbook of modern city planning’ (p84 Ladd). An early translation of one of his essays into English was The Cleaning and Sewerage of Cities published in New York in 1891 (wiki). He ‘intended his book to enlighten not only his fellow professionals but also “every educated citizen” (p178 Wagenaar)’. The Austrian Camillo Sitte’s much praised 1889 book , Der Städtebau nach seinen künstlerischen Grundsätzen (“City Planning According to Artistic Principles”, often translated as “The Art of Building Cities”) which aimed ‘to put planning into the hands of artists and architects was consistent with his argument for the applicability of models from the past’ (Ladd, p. 136). Sitte’s intention was to re-introduce the artistic dimension in urban planning, which he believed it had lost. While Baumeister focused on housing and traffic, seeking practical solutions for the hardships caused by urban growth, Sitte concentrated on the restoration of the city as the expression of a harmonious culture ... Sitte blamed the loss of urbanism’s artistic qualities on a rational mentality that tried to solve all problems in a “mathematical” way’ (Wagenaar, p. 188).